Dr. Hasan Shanawani was overcome by frustration. So, last week he picked up his cellphone and began sharing on Twitter his family’s enraging experiences with the U.S. health care system.

It was an act of defiance — and desperation. Like millions of people who are sick or old and the families who care for them, this physician was disheartened by the health care system’s complexity and its all-too-frequent absence of caring and compassion.

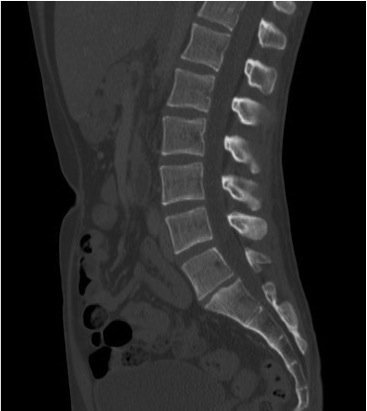

Shanawani, a high-ranking physician at the Department of Veterans Affairs, had learned the day before that his 83-year-old father, also a physician, was hospitalized in New Jersey with a spinal fracture. But instead of being admitted as an inpatient, his dad was classified as an “observation care” patient — an outpatient status that Shanawani knew could have unfavorable consequences, both medically and financially.

On the phone with a hospital care coordinator, Shanawani pressed for an explanation. Why was his dad, who had metastatic stage 4 prostate cancer and an unstable spine, not considered eligible for a hospital admission? Why had an emergency room doctor told the family the night before that his father met admission criteria?

Sidestepping Shanawani’s questions, the care coordinator didn’t provide answers. Later, another senior nurse in the hospital unit didn’t respond when he asked her to find out what was going on.

Inflamed, Shawanami let loose on

Twitter.

Within hours, Shanawani’s posts were widely shared and other people, some of them also doctors, recounted similar experiences. Within days, he had thousands of followers, up from fewer than 100 before his tirade.

Physicians wrote that Shanawani’s posts about observation care opened their eyes to the adverse impact it can have on patients and families. (When someone is in observation care, he or she can face copayments for individual tests and medical services under Medicare Part B — expenses that can quickly add up. Also, Medicare will not pay for short-term rehabilitation in a skilled nursing facility for observation care patients.)

Shanawani’s distress revolved around three key issues, he explained in a lengthy conversation.

- Hospital staff didn’t acknowledge his family’s concerns or address them adequately: How can an old man with terminal prostate cancer and a broken back be sent home without measures to ensure his safety?

- No one seemed to care or be willing to listen: When family members asked that lower doses of painkillers be administered to Shanawani’s father, who had become delirious during previous hospitalizations, they felt nurses were disapproving and disrespectful.

- And the decision to put his father in observation care was misguided and handled curtly.

There were two options for his father, the physician said: vertebroplasty, a surgery in which a bone cement is injected into the spine, or a fitted spinal brace. Shanawani’s father and the family decided against surgery but were told that he couldn’t receive a brace in the hospital because that option was available only to inpatients. Outside the hospital, it would take time to arrange an appointment with a spine specialist and get a brace. In the meantime, with an unstable spine, “my father was at risk of permanent paralysis,” Shanawani told me.

Because Shanawani has declined to identify the hospital in question, indicating only that it placed highly in U.S. News and World Report’s

rankings and was based in New Jersey, the institution’s perspective on these issues cannot be shared. It is possible that the hospital’s explanations would cast the physician’s story in a different light.

But Shanawani’s experiences are, by all accounts, widespread. “I wish I could say that this was in any way unique or an isolated event,” said Dr. Richard Levin, chief executive of the Arnold P. Gold Foundation, which focuses on humanism in health care, who reviewed the physician’s Twitter stream. “But his description of a broken system is so common.”

Theresa Edelstein, vice president of post-acute care policy and special initiatives at the New Jersey Hospital Association, acknowledged that “we need to focus on and be better at” attending to the “humaneness and patient-centeredness of care.” She made it clear this was a general comment, not a response to the situation Shanawani had described.

“If a patient is expressing concern about their observation status, the whole [hospital] team should be involved in understanding what the concerns of the patient and the family are,” Edelstein said.

Currently, patients with Medicare coverage cannot appeal a hospital’s decision to place them in observation care. The Center for Medicare Advocacy and Justice in Aging have filed a class-action suit in U.S. District Court in Connecticut seeking to establish such an appeal right. After years of litigation, a trial date has been set for mid-August, according to Alice Bers, the lead lawyer for the plaintiffs and litigation director at the Center for Medicare Advocacy.

But all patients have the right to a safe discharge under a separate set of regulatory requirements, and that can be grounds for an expedited appeal, Edelstein noted.

Ultimately, a physical therapist made it possible for Shanawani’s father to be admitted to the hospital once he failed a test she administered. And a palliative care nurse gave the family the sense of being cared for, which they so desperately needed. “She was a ‘one-in-a-million’ person,” said Shanawani, weeping as he spoke of her. “She said ‘We will fix this, we will figure this out with you, we’re working on the same side of the table.’”

“It takes just one person to really listen to make a profound difference in a patient’s care,” said Grace Cordovano, a professional patient advocate at Enlightening Results LLC in West Caldwell, N.J.

Social media outlets such as Twitter and Facebook are a powerful new avenue for people to seek redress for health care grievances, Cordovano noted. “If you tag a facility, a customer service representative typically responds quickly with ‘Please message me. We’re sorry you’re experiencing this, we’d like to help.’ Often, you get a better response than by going through the normal chain of command.”

Shanawani’s position — he’s deputy chief informatics officer for quality and safety at the VA — helped generate a high-level response to his tweets. New Jersey’s commissioner of health, Dr. Shereef Elnahal, a former colleague of his, reached out to the hospital’s leadership, and meetings with the CEOs of the hospital and its parent system followed. Also, the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions has asked Shanawani for his input.

“I have incredible privilege, and I know how to navigate bureaucracies,” the physician told me. “But still, hospital staff provided us no guidance, no assurance, no knowledge, until two people willing to help came along. I don’t know how to fix this.”

For now, this physician has other things on his mind: On April 30, his father took a turn for the worse and was rehospitalized. Shanawani knew this was likely at some point, but he had hoped it wouldn’t be so soon. “It starts all over again,” he wrote to me in an email